Concussion in College Students

Table of Contents

Return-to-Learn Stages | Considerations for Athletes

The Accommodations Process | Accommodations and Adjustments Guide

College Educators & Administrators

Concussion guide for College Educators

Friends | Sports and Club Captains | Residential Assistants

Overview

As a college student, concussions pose a particularly unique set of challenges. Students with concussions must navigate both academic and social environments on top of everyday responsibilities and post-concussion self-care needs. It can often be difficult to find resources on campus that provide adequate accommodations. However, it is often even more challenging to advocate for these accommodations to professors, coaches, administrators, and other people who might not understand the extent of this invisible injury.

Various ways a student may sustain a concussion on campus include—but are not limited to—sports-related activities, car accidents, falls, and random bumps or jolts to the head. Although concussions are often associated with sports-related injuries, more concussions throughout the academic school year are not sports-related. During the academic school years of 2016-2017 and 2017-2018, an average of 132.4 per 10,000 college students suffered a diagnosed concussion each year. It is likely that there were a significant number of undiagnosed concussions as well.

One common misconception is that concussions can only occur as a result of a direct hit to the head. A jolt to the body can cause the brain to move and/or twist in the skull. Sudden jolts are a significant contributor to the prevalence of concussions, particularly with regard to car accidents or other whiplash-inducing incidents. During college, the brain is still developing, so seeking treatment and proper care is especially important.

The geographic area of the college campus (rural, small town, or urban) and whether students are residential or commuting may impact the accessibility of certain resources. Many schools have a response plan for concussions and other brain injuries, as well as other healthcare resources that are beneficial during the process of rehabilitation. However, regardless of a student's living status, they may need to seek treatment from clinics outside their university system, depending on their health insurance options. General resources for individuals who have sustained a concussion can be found on our Guidelines for Recovery page. Additionally, the Resources section of this page has additional helpful information specific to college students.

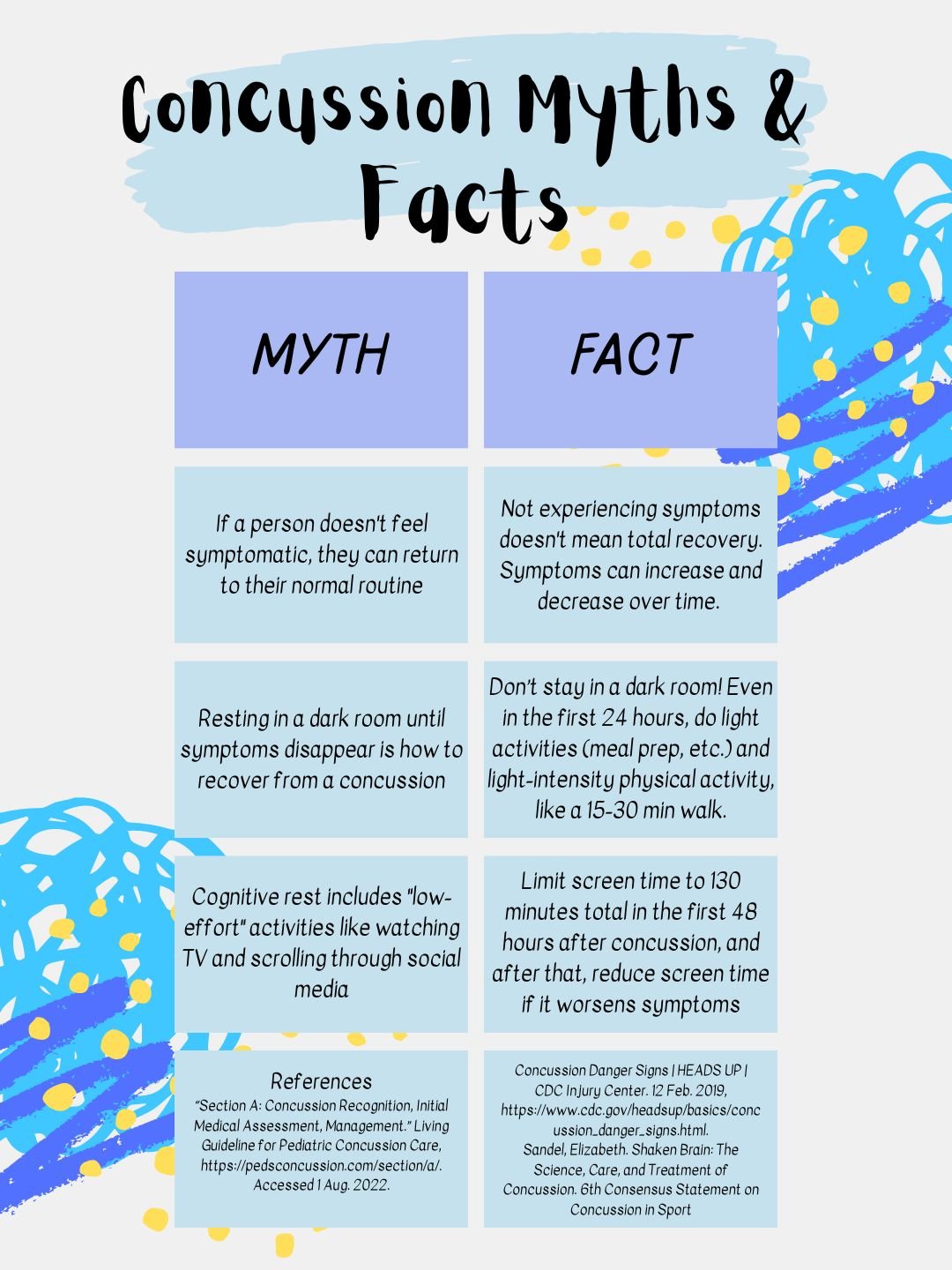

Concussion myths

Despite the unfortunate prevalence of concussions, many myths surrounding the injury are perpetuated by a lack of information regarding concussions. Some of these myths can even be detrimental to the recovery process. Hopefully, by understanding the truth behind this brain injury, students with concussions will be more likely to experience a more efficient, more successful recovery.

Symptoms and Red Flags

Concussion symptoms vary from person to person. Some common concussion symptoms include blurred vision or seeing stars, headache, confusion, anxiety, poor balance or coordination, dizziness, lightheadedness, tiredness, feeling sick or nauseous, increased emotionality, sleeping more or less than usual, difficulty sleeping, and difficulty remembering or concentrating.

While symptoms vary, red flag symptoms require immediate medical attention, as they may indicate a more severe brain injury, including bleeding or swelling of the brain. Red flag symptoms include any loss of consciousness, seizures or convulsions, slurred speech, vomiting, severe or increasing headache, neck pain or tenderness, weakness or tingling/burning in the arms or legs, becoming increasingly restless, being agitated or combative, one pupil being larger than the other, double vision, and deteriorating conscious state.

Symptoms vary significantly among concussion patients in terms of the type of symptoms, severity, and duration. Some symptoms may appear immediately, while others may appear days or weeks after the initial injury. A concussion patient may feel fine one day but worse the next. Many concussion patients will recover within 2-4 weeks. Symptoms that persist beyond 4 weeks are considered “persisting symptoms” and should be evaluated with a multimodal clinical assessment, and a referral for rehabilitation may be appropriate. While many recover within 2-4 weeks, between 11.4% and 38.7% of concussion patients will have lasting symptoms, referred to as persistent post-concussion symptoms (PPCS), or persisting symptoms after a concussion, formerly referred to as post-concussion syndrome (PCS).

This figure describes standard and red flag concussion symptoms. Red flag symptoms require immediate medical attention. Visual created by Kaori Hirano (2022 Concussion Alliance Intern).

Return-to-learn

Returning to activity after a concussion is difficult, especially for a college student. The process of returning to schoolwork is called return-to-learn. Return-to-learn is a series of steps that gradually return a student to academic work based on their symptoms. Return-to-learn has been heavily studied in children but less so in college-aged populations. This means that most of the current recommendations are directed toward grade-school students; however, many recommended strategies for returning to schoolwork can be applied to students of all ages. We have additional blog posts about return-to-learn research here, here, and here.

In the return-to-learn process, college students reported a variety of academic-related symptoms. These symptoms included difficulty concentrating and remembering, sensitivity to light and noise, drowsiness, headache, dizziness, and feeling “slowed down.” They also found reading, engaging with computer/projector screens, and paying attention to instructors to be especially difficult.

College students experience a variety of symptoms when returning to learn. The prevalence of symptoms is detailed in the figure, which was created by Kaori Hirano (2022 Concussion Alliance Intern).

About Return-to-Learn Stages

Because few guidelines exist for college students, Concussion Alliance developed the return-to-learn strategy below. To maximize the relevance of this return-to-learn strategy, we engaged with different collegiate stakeholder groups: students who experienced concussions while in college, a disability peer leader, a varsity sports team captain, and college administrators. The stages are partially adapted from Parachute Canada’s Guideline on Concussion in Sport, US Air Force Academy’s Return-to-Learn and Northwestern University’s Concussion Management Plan, the Concussion Awareness Training Tool E-Learning Course for Parent and Caregiver, and Achieving Consensus Through a Modified Delphi Technique to Create the Post-concussion Collegiate Return-to-Learn Protocol.

Return-to-learn consists of several stages that increase cognitive tasks while minimizing symptoms. The first stage is 24-48 hours; for the rest of the stages, the amount of time for each stage will vary for each student, and some stages may take longer than others. At a minimum, each stage should be 24 hours. A student can move to the next stage when they can tolerate the activities in the current stage without new or worsening symptoms. For the student to move on to the next stage, symptoms do not have to disappear completely.

If symptoms reappear or worsen, the student should stay at the current stage for at least an additional 24 hours or move back a stage. Keep in mind red flag symptoms: If these are present, seek medical care immediately.

Learn more in our Guidelines for Recovery regarding what to do if symptoms persist. International guidelines say that symptoms are “persisting” if they last longer than 4 weeks, at which point active rehabilitation guided by a collaborative team of healthcare providers is recommended. For some types of symptoms, early medical or rehabilitative intervention is recommended; “if dizziness, neck pain and/or headaches persist for more than 10 days, cervicovestibular rehabilitation is recommended.” Additionally, for vision issues that persist beyond 4 weeks, it is recommended to seek care; see our Vision Therapy resources.

Return-to-learn stages

Immediately After Injury

Important first steps (you may want to ask a friend or other support person for assistance):

Seek immediate emergency medical care if you experience any red flag symptoms (e.g., severe or worsening headache, slurred speech, persistent vomiting; see our Symptoms and Red Flags section to read more.

If a concussion is suspected during practice, game, or other physical activity, you should remove yourself from that activity; you should not return to play or get back on the bike, etc.

All concussion patients should see a medical provider as soon as possible, ideally within 24-72 hours of their injury. You should not drive until cleared by a medical professional.

Begin building your community and academic support network (see the end of this document for details).

Contact any peer supports that may be helpful (student wellness leaders, resident advisors, class teaching assistants, club presidents, sports captains, etc). Let them know that you have a concussion and may need help or support in the coming weeks; you should stay in contact with your team throughout the return-to-learn process.

Your dean or accessibility staff should begin the accommodations process upon notification. Read our Accommodations & Adjustments Guide for College Students for more information. We also have a Concussion Guide for College Educators, which includes a list of concussion adjustments that professors and college staff can offer students.

Notify instructors that you will need to miss class until you complete Stage 2 of this return-to-learn strategy and may have to miss further classes going forward, depending on your recovery timeline.

Stage 1: 24 - 48 hours of Relative Rest

Goal: Tolerate activities of daily living

“Relative Rest” – Light Cognitive/Physical Activity: Immediately after your concussion and for the first 24-48 hours, you can do daily activities such as light (non-schoolwork) cognitive activities like easy reading, light physical activity like walking, and visiting with friends in a calm environment. Start with 5-15 minutes at a time and increase gradually. If you have not yet already, notify your instructor about absences and/or inability to complete course assignments. Don’t attend class or do schoolwork.

Use symptoms as a guide

During all daily activities (physical and cognitive), a mild and brief increase in symptoms is good for your recovery–remember, this is a rehabilitative injury. However, symptoms should not increase more than 2 points out of 10 during the activity and return to pre-activity levels within an hour of stopping the activity. If the symptoms don’t return to pre-activity levels within an hour, then reduce the level of that activity the next time you do it.

Screens

Limit screen time, ideally, to an hour per day in the first two days. In one study, patients who limited their screen time to 65 minutes a day for the first two days recovered in half the time compared to patients who did not limit their screen time. Screen time includes cell phone, TV, and computer usage. If symptoms worsen due to screen time, take a break from the activity that is exacerbating them. Consider keeping another light source on during screen time, especially if screen time worsens symptoms. Talk with your instructor about options to limit screen time for future assignments or coursework.

Dining Halls or Other Noisy Environments

It may also be helpful to eat meals in your living space or another quiet area to avoid dining halls, or eat in dining halls during periods when fewer students are present. Dining halls can be overwhelming and overstimulating for people with concussions, especially during peak hours. This may also be relevant for other noisy environments, such as music rooms, assemblies, student union buildings, or other crowded and busy locations.

Begin discussing academic adjustments or accommodations with your accessibility resource office and instructors. Refer to our Accommodations and Adjustments Guide for accommodations and self-care strategies for yourself. It may be helpful to send your professors our Concussion Guide for College Educators, which provides education about concussions and the recovery process, as well as examples of accessibility adjustments.

Stage 2: School-Type Work Outside of Class

Goal: Increase tolerance for cognitive activities

School-Type Work Outside of Class/Gradually Increased Physical Activity: You can start doing school-type work in short chunks of time, such as assignments or readings, with modifications as necessary, as you can tolerate. Start with 30 minutes of work with a 15-minute break afterward, and gradually increase time as tolerated. You should not attend class during this stage. You may progress to Stage 3 if you can tolerate schoolwork-specific cognitive activities outside of class for roughly the duration of a class (60 minutes) without symptoms increasing by more than 2 points out of 10.

How to do physical activity safely

Physical activity (such as walking) should not result in more than a mild and temporary symptom increase. Do not do any activity that poses a risk for a fall, collision, or blow; no bicycling, contact activities, etc. Many concussion patients experience dizziness and balance issues, which increase their risk of falling during physical activity. Consider ways to increase the safety of your activity (stationary or recumbent stationary bicycle, treadmill, walking with a buddy, etc.). You may need to work collaboratively with instructors to adjust any courses you’re taking that require physical activity (e.g., PE courses, field labs, etc).

The return-to-learn and the return-to-play can occur together, but return-to-learn needs to be completed before full return-to-play.

Screens

Continue to use screens as tolerated. If you need other accommodations to reduce screen time, be sure to communicate with your professors or academic advisor about non-screen options (assigned note taker, physical print-out copy of the lecture or assignments, etc.).

Stage 3A: Part-time School (Light Schoolwork Load, No Testing)

Goal: Increase tolerance for academic activities

Part-Time School, Light Load: Start building your level of cognitive activity, taking breaks as needed. Begin doing partial days of classes, taking breaks as needed. It may be easier to avoid classes that may lead to the onset of symptoms, such as classes with labs, excessive computer use, or more challenging material. Testing and exams are not recommended during this stage, and students should work with their instructors and the Accessibility Office to create a personalized and flexible exam timeline. When able to tolerate a partial class schedule and schoolwork outside of classes for longer chunks of time (e.g., ~120 minutes) without new symptoms or symptoms increasing more than 2 points out of 10, advance to Stage 3B.

Stage 3B: Part-time School (Moderate Schoolwork Load, Modified Testing)

Goal: Tolerate a regular class schedule with (modified) testing

Introduce limited testing with adjustments or accommodations (e.g., extra time, reduced distraction testing environments, open-note options).

Attend more class sessions, working toward full school days.

Increase schoolwork outside of class.

Reduce learning accommodations as needed, though it’s always an option to ask for the accommodation back if reducing an accommodation feels like it’s slowing recovery or increasing symptoms.

Move on to Stage 4 once you can tolerate attending most classes and keep up with (lightly modified) assignments.

Discuss rehabilitative treatment options with your medical provider if you are not progressing through this protocol within 2-4 weeks, you have symptoms that have not improved, or your symptoms continue to worsen during cognitive activities (especially schoolwork, classes, or exams).

Stage 4 Progression to Full School Workload

Goal: Tolerate full academic course load

This stage involves returning to nearly normal cognitive activities and doing routine schoolwork and homework as tolerated. Accommodations and adjustments may be further reduced during this stage. When you are able to tolerate a full-time class schedule, academic load, and normal testing environment without more than a mild worsening of symptoms, the return-to-learn process has ended.

Notes About the Recovery Process

Further academic modifications may be necessary if the student experiences prolonged symptoms that necessitate the student not attending class for an extended period and may require a medical leave of absence from school, as determined by the student’s medical team.

Details about your multidisciplinary team

Be sure to work with your multidisciplinary team to help coordinate and keep communication lines open regarding decisions to progress, regress, or maintain the status quo during the return-to-learn process. Your multidisciplinary team may include but is not limited to physicians, athletic trainers, academic advising staff, coaches, administrators/professors, and your personal community of friends, family, and peer support.

Your multidisciplinary team may include the following:

Medical Team: primary care physician, sports medicine or brain injury medicine physician, mental healthcare professional (psychologist or other behavioral health providers), and athletic trainer (if relevant).

Academic Team: campus academic advisor, assistant dean of students, accessibility office, academic dean, instructors–and (if relevant), athletic academic advisor, faculty Athletic Representative.

Community Team: roommates, parents, siblings, and close friends–and (if relevant) teammates and coaches.

“The key to this process is listening to the body and not trying to push through worsening symptoms but accepting when the body and brain say they need a break.”

Considerations for Athletes

Keep in mind that many schools have a concussion management plan in place for college athletes. If a student is a college athlete and suspects they have a concussion or have been diagnosed with a concussion, consider checking with the school’s athletic department to see if there is a pre-existing return-to-learn and return-to-play protocol. Additionally, student-athletes and students with highly active lifestyles are recommended to seek out aerobic exercise tolerance testing followed by prescribed aerobic exercise treatment as early as 2 days after injury (PedsConcussion, under section A, scroll down to Initial Medical Assessment and Management, click on Recommendations, scroll to section 2.3d). This can help determine their exercise tolerance early on and influence their recovery process, which may slightly alter the individual’s return-to-learn process.

Self-advocacy

One key difference between return-to-learn in a college setting versus a childhood setting is the level of self-advocacy. Self-advocacy is a person’s ability to speak up for themself and the things important to them. For a concussion, this means being able to discuss your concussion and concussion-related symptoms, and working with your institution to find reasonable adjustments and accommodations. College life gives students more freedom and less structure; they often live away from home and determine their own schedule, meals, and study time. In college, students may have different support structures than in high school, such as less involvement from parents/guardians, teachers/professors, and school administrators. This is not to say that support structures do not exist for college students! There are many people there to support college students in meeting their needs, but the student typically needs to be the one to seek out these supports, making self-advocacy an essential skill.

The Americans with Disabilities Act

An essential part of self-advocacy is knowing one’s rights and being able to speak up for them. The most important information regarding rights in the college environment is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) for students in the United States. ADA serves to protect Americans with disabilities from disability-based discrimination. Brain injuries, including concussions or mild traumatic brain injuries, are recognized as a disability under the ADA. A Mayo Clinic pdf explains that brain injury, including mTBI (concussion), is covered by the ADA. Even if a school doesn’t list concussion or mTBI as a disability, they are still required to provide reasonable accommodations. Even for the majority of concussion patients whose symptoms are temporary, these symptoms still constitute a (temporary) disability and should be treated as such by both the school administration and the students themselves.

Identifying a concussion disability with the Accessibility Office

Under ADA, colleges are required to provide qualified students with reasonable accommodations. Students are the ones who initiate the accommodations process by identifying as a student with a disability to their Accessibility Office. When seeking accommodations, students are required to provide their educational institution with the necessary documentation of their disability. A student is not legally required to disclose their disability, but documentation is necessary for them to be qualified for accommodations under ADA. A reasonable accommodation is a change that allows the student with a disability to participate equally in the college environment without placing undue hardship on the institution.

Accommodations

In the process of recovering from a concussion, many students will receive varying accommodations to support them. The number and type of accommodations a student will have are specific to their unique recovery, so having few or many accommodations is entirely normal.

Adjustments to learning and living situations may be a better course of action for students whose symptoms resolve within those two weeks than formal accommodations. Return-to-learn management becomes more difficult when the student has symptoms that last longer than two weeks. For students whose symptoms don’t resolve or aren’t expected to resolve within two weeks, accommodations will be an essential part of recovery.

Reasonable accommodations enable students with disabilities, including those with concussions, to have equal opportunities to participate in college life by making modifications to courses, programs, services, jobs, activities, or facilities. For more information on reasonable accommodations, we recommend Self-Advocacy and the Transition to College, a great introduction to self-advocacy for college students.

These accommodations are not only for academics. Accommodations aim to remove barriers in the college environment, from the classroom and work environment to the dining halls and dorms. Accommodations are obtained through the college Accessibility/Disability Office. On some campuses, accommodations may be obtained in collaboration with a variety of offices, such as the Dean of Students Office.

Adjustments

Adjustments, like accommodations, are modifications that last while the student recovers from their concussion. Adjustments often make more minor changes but are no less important. In some cases, adjustments may be a better option than accommodations, depending on the student’s situation and school.

The institution’s Accessibility Office may implement accommodations and arranging for adjustments may be done by the student themself.

Examples of adjustments:

A conversation with a professor about sitting closer to the front of a lecture

Asking an RA to manage dorm noise levels better

Academic adjustments

wearing a hat in class to block overhead light

asking a professor for additional time on an assignment/exam.

The Accommodations Process

Some schools may already have processes for assisting students with concussions, so check a school’s Accessibility Office webpage for more detailed, school-specific information. For example, some schools may have informal accommodations available for several weeks and implement formal accommodations if symptoms are persistent or recovery takes longer than a few weeks.

The key steps in the official accommodations process are often similar and are outlined below.

Reach out to the school’s Accessibility Office. Scheduling a meeting with the Accessibility Office is essential to getting accommodations. Gillette Children’s Hospital says, “it’s essential to communicate with the designated disability services office or disability services coordinator in order to receive the accommodations you need.” Information on this office should be on the college website. If there is difficulty locating this, try reaching out to an advisor, professor, or residential assistant (RA).

Obtain medical documentation from a healthcare provider/medical professional. The documentation can be sent from wherever the concussion was diagnosed and should list the concussion diagnosis and the date of injury. Documentation may be provided by a local medical clinic, on-campus health center, or if the student is an athlete, by an athletic trainer. It may be helpful to reach out to the college’s Accessibility Office or check their website to find out if they require additional documentation.

Prepare questions, concerns, and accommodation ideas. After scheduling a meeting, consider the goals of the meeting. Consider what accommodations are needed to succeed in college life in terms of academics and daily living. Examples of accommodations are provided in the Concussion Alliance Student Accommodations Guide.

Meet with the Accessibility Office. This meeting can be in-person or, if better for the student’s symptoms, online. Bringing pre-written questions or ideas may make the discussion more comfortable and reduce nervousness. Taking notes can also help recall details from the meeting later on, which may be especially helpful for students affected by memory or concentration issues. One key thing to discuss is how instructors/professors will be notified about accommodations.

Discuss accommodations with instructors/professors. Many institutions will notify course instructors about a student’s accommodations. Some students may feel more comfortable discussing their accommodations with professors, in addition to the school notifying instructors, while others do not. Doing this is completely optional and entirely dependent on what the student feels comfortable with.

Students can direct professors to the Concussion Alliance Concussion Guide for College Educators and the Educators & Administrators section of this page for more information. For more guidance on how to approach talking to professors, lesson 8 of Self-Advocacy and the Transition to College has tips and conversation examples.

Continue communicating with the Accessibility Office. As symptoms change, so should accommodations. Remember, there is no set timeline for recovery. Many people will recover in a few weeks, while some take months. Other concussion patients have persistent symptoms years later. Because of this, return-to-learn timelines will vary from student to student and should adapt to fit a student’s current needs.

Accommodations and Adjustments Guide

If this information feels overwhelming, try looking through this simplified Accommodations and Adjustments Guide for College Students with a summarized version of the above content, plus adjustment and accommodation ideas to help get started.

College educators & administrators

The role of the college educator with a concussed student is usually peripheral and responsive. A school’s Accessibility Office develops return-to-learn plans in conjunction with the student; this plan helps students succeed in the college environment. While educators typically don’t play a role in developing this plan, they still play an important part in implementing the plan’s academic accommodations.

Unlike illnesses like the flu, students cannot continue their workload as usual and should not work at all in the early stages of recovery. Reduced cognitive load, which minimizes tasks requiring mental exertion, is integral to concussion management. A student’s symptoms can be physical, cognitive, and emotional and manifest in various ways. Symptoms often differ from student to student, meaning accommodations and return-to-learn will vary from student to student.

Remember that concussions are invisible injuries. It is impossible to tell how injured or recovered a concussion patient is by looking at them; the only way to know this is by listening to and believing the student’s experience. Students should not have to justify, convince, or prove their symptoms or the need for their accommodations. The role of the college educator is to listen to the concussed student and their school’s Accessibility Office to facilitate the student’s successful return to the classroom.

Throughout this process, be open to hearing how to make the classroom environment more accessible. For more information on how to make the classroom better for students with concussions and more accessible in general, an article published in Collected Essays for Teaching and Learning has recommendations on how to make all classrooms, virtual and in-person, better for students.

College Administrators, College Concussion webpage

For school administrators, consider creating a school resource page for students with concussions. This way, students can easily access the school’s resources. Luther College’s “Concussion Process for Students” is an excellent example. Their website briefly lists what students should do after being diagnosed with a concussion. Ideally, a concussion resource page has links to campus wellness, mental health, accessibility resources, the location of offices for further information (such as the Dean of Students Office), and suggested options for obtaining a concussion diagnosis, such as nearby health care providers.

Concussion Guide for College Educators

Concussion Guide for College Educators is a short, what-to-know document about concussion management in a college setting that can be shared with college faculty to increase understanding of concussion and the return-to-learn process in college students.

Social life

While it’s easy to get caught up in the fast-moving pace of social life in college, it’s necessary to put personal health first. Big gatherings, alcohol and other substances, and overstimulation in general can worsen concussion symptoms and lead to a prolonged recovery. However, maintaining relationships and balancing social life is essential for any college student and maintains support through the challenging process of concussion recovery. There are some aspects to be particularly careful of—such as alcohol and other substances, as well as overstimulating environments—but a concussed student can take measures to enable participation in social events.

Alcohol and Drugs

Studies have found that 20% of persons with TBI develop a substance use problem for the first time following their injury. Substance use is dangerous in itself and can also lead to detrimental changes in brain structure and function in a person who has a TBI. Alcohol consumption following a concussion can prolong recovery time. And because alcohol is a neurotoxin, it can damage brain cells and affect the delicate balance of chemical processes in the brain. This is especially harmful as the brain attempts to heal neuronal connections during the healing process after a concussion.

Below is a list of effects caused by drug use that are specific to people who have sustained a TBI.

Don’t Recover As Well

Problems in Balance, Walking, and Talking

Say or Do Things Without Thinking First

Problems With Thinking, Concentration, or Memory

More Powerful Effect of Substances After TBI

More Likely To Feel Low or Depressed

Can Cause a Seizure

More Likely To Have Another TBI

A few of the major issues caused by alcohol particular to people suffering from traumatic brain injuries.

Note: A more in-depth explanation is provided in the PDF “How does alcohol and other drug use affect a person who has had a TBI?” on the Wexner Medical Center website.

Overstimulating (loud or overly bright) environments

Along with substances, loud environments—as a result of music or many people talking at once—are common in social scenes. This can be difficult to navigate. However, there are ways to still participate in these scenes without being negatively impacted by these factors. The Sensory Sensitivity section of the Concussion Alliance website has helpful tips and tricks to steer around sensory difficulties. Earplugs and headphones are recommended to circumnavigate loud noises, and hats or sunglasses are suggested to prevent bright, colorful lights from bringing about or worsening symptoms.

Buddy System

Another helpful tip is to create a “buddy system” with one or more friends. This way, a few friends will know to check in at various points in time and recognize if any symptoms are starting to appear. Finding alternative activities to enjoy with friends is another possible solution for engaging in social events without negative consequences. Some possible activities include board games, puzzles, long walks, and movie nights (as long as the light stimulation is not an issue).

Dining Halls

A difficulty that may not be apparent until later is issues with dining halls. Dining halls can be loud, busy, and overstimulating in various ways. If possible, a concussed student should see if there is an opportunity to visit the dining hall during non-busy hours, take the food to go or have a friend pick up food and deliver it. If none of these options is possible, previously mentioned suggestions for navigating overstimulating environments—utilizing earbuds, sunglasses, and hats—are also useful in this context.

Peers

Friends

Watching a friend go through the concussion recovery process can be challenging as well as hard to understand. The most important thing to remember is that everyone goes through the recovery process differently. Concussions are not a "one-size-fits-all" deal; there might be a wide range of symptoms that vary in severity. The symptoms and needs of a concussed person may be consistent or may change daily—a friend's job is to be there for a concussed friend and support them in any way they may need.

While it is considerate to ask a concussed friend what they might need or what you can do for them, this well-intended favor may put pressure on the concussed person to try and figure out what can be done, even if they might not know how to help themself. Sometimes, there isn't anything that a friend can do besides sit and keep a concussed person company. Furthermore, there might be times when a concussed friend needs space. This is never personal, and it's always a good idea to remember, after giving them some space, to check in on them later.

Big social gatherings—such as parties or large campus events—can be physically and mentally intimidating and stressful for a concussed person. Instead of attempting to "tough it out," there are many activities that a concussed person can participate in without experiencing an increase in symptoms. A friend can suggest activities that would be enjoyable for both parties. Below is a list of activities that might provide a concussed person some relief from the difficulties created in other social scenes:

Sewing or knitting

Meditation

Scrapbooking

Cooking

Walking

Yoga

Board games, puzzles

Stargazing

Painting

A person suffering from a concussion may be more irritable and may experience mood swings, increased emotionality, anxiety, and depression, all of which can be trying on a relationship. As a friend, know that a concussed person might act differently than before, and there's no exact timeline for recovery. Try not to take things personally, and remember to be patient when maintaining a healthy friendship.

Sports and Club Captains

Sports captains and club captains should be aware of the changes and difficulties that a team member might be going through during this process of recovery. As a leader, it’s crucial to be educated more deeply about concussions and understand the process of recovery, and for those with persistent symptoms, the rehabilitation process. There are many free resources available, one being the NCAA Concussion Fact Sheet for student-athletes which the NCAA and CDC created. Although it is specifically geared toward athletes, non-athletics-related groups can take advantage of the information provided.

Knowing the basic signs and symptoms and the possible causes of a concussion can be helpful, especially if the team member does not know that they are suffering from a concussion.

Additionally, pressure from coaches, teammates, and their internal pressure may prevent a person with a concussion from reporting their brain injury. However, if a leadership figure encourages their team or club to put each individual’s health before the outcome of any competition, it will create an atmosphere in which people feel comfortable seeking help. Simply understanding that your teammate or fellow club member is going through a difficult time and that they need extra support is essential for allowing them an opportunity for the best possible recovery process.

Residential Assistants

Unfortunately, many schools do not provide concussion-specific training as part of the general RA training process. However, as someone whose job is to guide and provide services to residents, being informed about concussions and different resources to offer to a concussed person can make a huge difference in a student’s life.

The accommodations process section of this page includes practical steps that a student with a concussion can take, including where they might find help on campus and how to communicate needs in the classroom and on campus in general. In the social life section of this webpage, there are many suggestions for how a concussed person can participate in social gatherings or alternative activities. Encourage a concussed resident to find ways to enjoy the college experience without significant overstimulation, which may delay recovery, or participating in activities that could cause further injuries.

Additionally, there might be times when a resident assistant has to take action in situations where music or voices from a large gathering in other rooms can be heard through walls. Even if it isn’t past “quiet hours,” an RA can remind other residents that the dorm is a shared space and that the noise may be detrimental to the well-being of others.

Hopefully, residents will be receptive and understanding. If not, the health and safety of a concussed person is a priority, and it may be necessary to get the Hall Director involved if residents are unwilling to make adjustments. Here is an example of an appropriate statement that a former RA suggested when approaching a difficult situation such as this one:

Hey, I just wanted to let you all know that your noise levels are totally fine, but we actually have some health issues amongst residents right now that make even muted noise challenging, so I’m seeing if our dorm would be willing to hold conversations and events as much as possible outside of the sleeping spaces and in our common areas instead. I will get some extra snacks for our kitchen to help make the common room more enjoyable! Any requests?

Mental health and resources

Balancing schoolwork, social life, extracurricular activities, and the everyday challenges presented by living independently in college is even more complicated when a person suffers from a concussion. Even without a concussion, up to 44% of college students experience symptoms of depression and anxiety. And of these students, 75% are reluctant to seek help.

Sustaining a concussion may mean that a student gets behind on work, cannot hang out with friends as frequently, or has a hard time focusing in the classroom and learning, all of which can significantly contribute to a decline in mental health. Studies show that approximately 1 in 5 individuals may experience mental health symptoms up to six months after a concussion. Usually, there are resources available on-campus, such as a variety of mental health services.

Still, it may also help to hear other people’s stories about their experiences with concussions, read about particular characteristics of mental health following a concussion, and understand more about the options available for helping treat mental distress caused by concussions. Below are resources on physical and mental health and people’s concussion stories.

Mental Health, The Invisible Injury, Overview of Self-Care, Social Support

Concussion Alliance resource pages specific to concussion

Hear other people’s personal experiences with concussions

Understanding Mental Health of Brain Injury Survivors

Read about mental health struggles following mTBI: signs, resources, helplines

Mental Health Disorder Information for Patients

Learn about the causes, diagnosis, and treatments for mental health issues resulting from concussions

Mental Health in College | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness

Read a brief overview of mental illness and mental illness management in the college setting

Effects of Brain Injury | Headway

Discover various effects of brain injury, such as behavioral and emotional effects, and ways to deal with them. Headway provides information for mild, moderate, and severe TBI but still has many great, applicable resources for people with concussions.