Individuals with a Pre-Existing Disability

Dr. Osman Ahmed, PhD, PGDip (Sports Physiotherapy), has reviewed this page for accuracy.

Angela Romeo, Disability Advocate, has reviewed this page for accuracy.

This resource includes up-to-date research on how pre-existing disabilities impact the diagnosis, treatment, and recovery from concussions. The information is relevant for individuals with a pre-existing disability, however, many sections have a focus on para-sport athletes and the blind or low vision community. We acknowledge that this page only begins to cover the topic, but we hope this resource is impactful for individuals with a pre-existing disability navigating a concussion.

Contents:

Identifying and Treating Concussion in Individuals with Disability

Athletes with Pre-Existing Disability: An Overview

Concussion Education for Athletes with Pre-Existing Disability

Concussion Testing for Athletes with Pre-Existing Disability

Return to Sport Guidelines for Athletes with Pre-Existing Disability

Interview with Paralympic Skier Millie Knight

Persisting Symptoms for Individuals with Pre-Existing Disability

Mental Health and Pre-Existing Disability

Disability Stigma and Navigating Healthcare

Overview and Introduction

Concussions are common but often deceptively complex injuries that pose unique challenges for individuals with a disability. According to the United States Census Bureau, close to 1 in 5 Americans live with a disability, and more than one billion people worldwide live with a disability. Epidemiologists estimate that, each year, 55.9 million concussions occur worldwide. Individuals with a pre-existing disability who sustain a concussion may struggle with inadequate testing and diagnosis, unusual symptoms, unique mental health challenges, and disability stigma in healthcare.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines disability as “physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. The term includes chronic and terminal illnesses; communication and neurological conditions; and developmental,hearing, intellectual, learning, psychiatric, physical, sensory, and vision disabilities. Disability can be visible or invisible, temporary or permanent, life-long or acquired.”

Identifying and Treating Concussion

These areas may be potential barriers and require specific considerations for concussion patients with a pre-existing disability.

Accurate testing and diagnosis: Certain concussion assessments need to be modified based on the individual's disability. Vestibular tests may need to be modified for paraplegic and blind/low vision individuals because oculomotor tests are not applicable. Blind/low vision individuals may need additional testing, including memory and cognitive tests, to compensate for providers’ reliance on visual assessment in concussion.

Recovery time: Recovery time may be prolonged for individuals with certain disabilities. Further research is still necessary to understand the long term effects and recovery trajectory for para-sport athletes, adaptive sport athletes, and all individuals with a disability.

Navigating health care: Individuals with disabilities can struggle with discrimination in favor of abled individuals (ableism) when trying to navigate health care. Because concussion symptoms may overlap with pre-existing symptoms, receiving a diagnosis can be more challenging. Check out our section below on tips for navigating healthcare with a pre-existing disability.

Disabilities with an increased likelihood for sustaining a concussion:

Individuals with the following disabilities may have an increased fall risk, or reduced ability to be aware of their surroundings. This poses the risk of running into other objects or people.

Individuals who are blind or low vision

Disabilities with increased fall risk such as those with developmental disabilities, gait dysfunction, muscle weakness etc.

Neurological disorders such as epilepsy

Intellectual disabilities

Athletes with Pre-Existing Disability: An Overview

Below we’ve outlined a list of organized sports federations that are present for individuals with disabilities:

Paralympic Movement: Some specific physical disabilities and blind/low vision

Special Olympics: Intellectual and developmental disability

Deaflympics: Deaf or hard of hearing

Adaptive Sports: Any disability

Popular para-sports

Sled Hockey

Para-Alpine Skiing

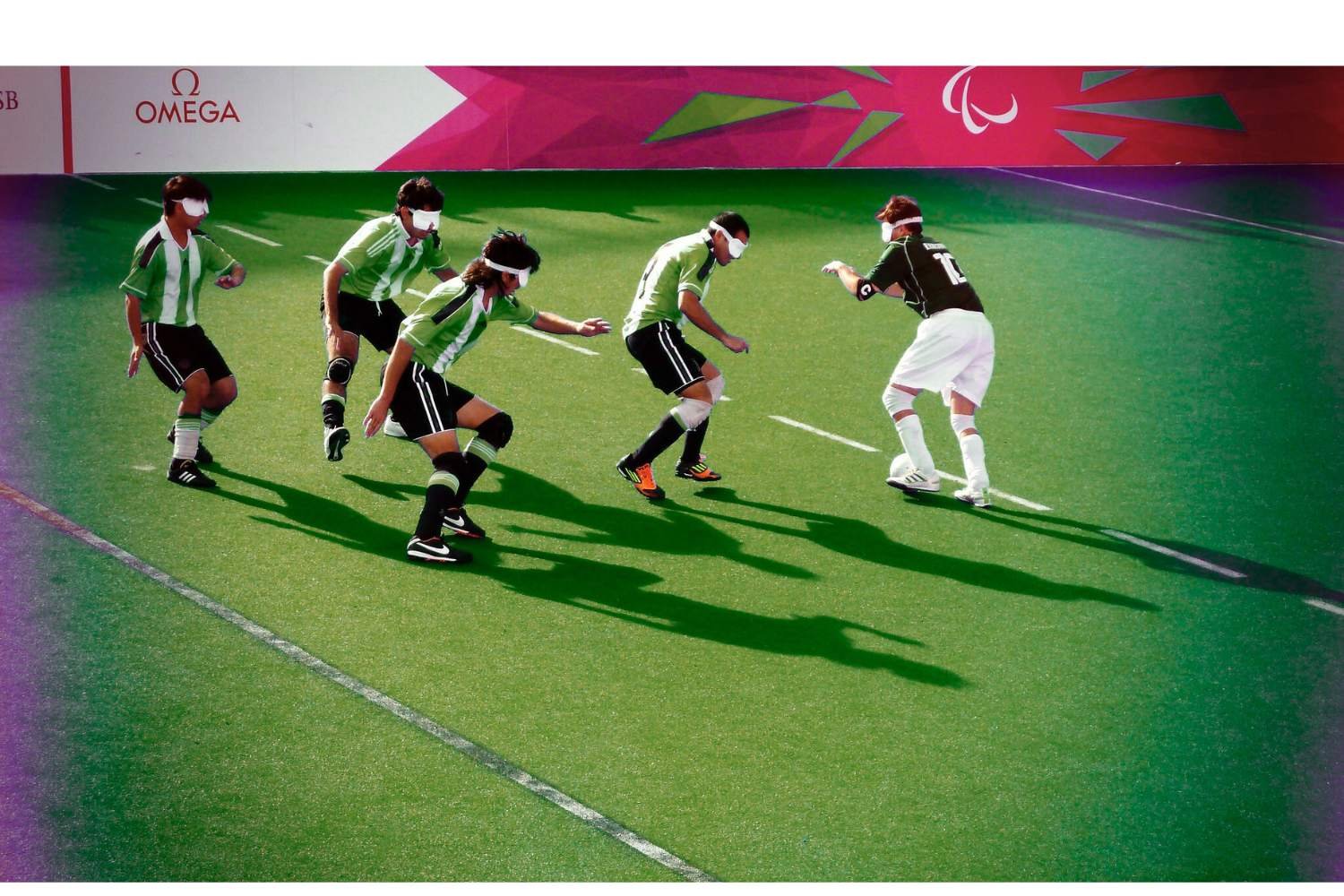

Blind Football

Para-Cycling

Wheelchair Basketball

Wheelchair Rugby

Para-athletes are individuals with impairments who play sports that have either been adapted for their impairment group or created specifically for it. Most of the current research on concussion in sport has been done on able-bodied athletes; however, new studies are beginning to understand the increased risk faced by para-sport athletes, and by extension, all athletes with disabilities. A concussion, also called a mild traumatic brain injury, is caused by a blow, bump, or jolt to the head, neck, or body that transmits an impulsive force to stretch, compress, and twist the brain, which alters normal brain functioning. Learn more about what happens to your brain when you sustain a concussion on our page here.

Concussion Education for Athletes with Pre-Existing Disability

Concussion education is a crucial component for the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and understanding of concussion for individuals with a pre-existing disability. Concussions are serious injuries that have the potential to lead to persisting symptoms. Educating athletes, clinicians, and sports staff about proper guidelines for assessment and treatment that is specific to athletes with a pre-existing disability is essential. Athletes should not be told to “shake it off” or feel pressured to return to the game. Coaches and sports physicians should always err on the side of caution if a concussion is suspected in an athlete. In addition, creating sports rules, providing protective equipment, and adapting sports equipment can increase safety for athletes.

Find out more about how concussions can impact future health from our website.

Concussion Testing

The SCAT-5 is a commonly used concussion test that may be used with specific alterations for athletes with a pre-existing disability. As of June 2023, the SCAT-6 has replaced the SCAT-5. Clinical judgment should be used in conjunction with applicable tests and should pertain to the individual's disability. For example, blind or low vision individuals have higher scores of symptoms on these concussion tests when compared to those without a disability.

Concussion assessment differs for individuals depending on their disability. Baseline testing should be conducted pre-season due to the fact that commonly available baseline tests like the ImPACT test are developed for, and used in research with, able-bodied athletes. Having accurate baseline data before injuries occur ensures the test's accuracy. Every disabled athlete will have different baselines, with significantly higher variance than in the able-bodied population. The SCAT-6 tests for several baseline functions that are often impaired in people with disabilities; these commonly include cognitive, visual, balance, and movement testing. For blind and low vision athletes, tests that include eye-tracking may be omitted.

When assessing for cervical spine injuries, extra caution should be taken during examination for athletes with down syndrome, achondroplasia, and osteogenesis imperfecta. Vestibular testing may not be accurate or possible in people with the following disabilities: arthrogryposis, post-polio syndrome, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, and spina bifida.

A working group of researchers and para-athletes called the Concussion In Para-Sport Group (CIPSG) published the following considerations for para-athletes as part of their first position statement on concussion in para-sport in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. This may also be more broadly applied to disabled individuals.

The importance of baseline testing because this will more accurately represent the changes in symptoms following concussion.

Individuals with central nervous system injury such as cerebral palsy or stroke may require an extended period of initial rest.

Recovery tools may differ in athletes who cannot use stationary bikes and treadmills.

Returning-to-sport protocols should be tailored based on the individual’s needs.

Return-To-Sport Guidelines

Return-to-sport guidelines are an essential part of providing safe concussion care for athletes. Dr. Osman Ahmed is a sports physiotherapist based in the United Kingdom and is a founding member of the Concussion in Para Sport Group. Dr. Ahmed consulted as part of the creation process of this resource. Below are the steps that the Concussion in Para-Sport Group outline for addressing concussion in para-sport athletes (read about this research here). Though this was formatted specifically for para-sport athletes, this outline may also be generally helpful for anyone with a disability who suffers from a concussion. Physicians must consider pre-existing disabilities and how they interact with concussion symptoms.

Recognize and Remove: If an athlete is suspected of having a concussion, they must immediately be removed from the game and assessed by a medical professional. Check for red flag symptoms such as neck pain, double vision, weakness or tingling in arms or legs, severe headache, seizures, loss of consciousness, and vomiting.

24-48 hours of relative cognitive and physical rest: During this time, athletes should not engage in strenuous activities and should limit screen time. Continuing daily activities and light movement are encouraged.

Increase Cognitive and Physical Activity: Athletes are encouraged to participate in aerobic exercise that elevates their heart rate. They are also encouraged to increase cognitively demanding tasks, all within a safe level of symptom threshold.

Safely return to sports and other activities: If daily activities do not exacerbate symptoms, a gradual return to sport includes a step-by-step progression to ensure safety for athletes.

Refer: If symptoms persist beyond 28 days, further treatment should be done to address the athlete's individual needs.

The online Concussion Awareness Training Tool (CATT) provides specific guidelines for blind/low vision athletes. This CATT training tool is the basis for our Return to Sport Guidelines Visual below.

Interview with Paralympic Skier Millie Knight

Millie Knight is a British Paralympic skier who competes in all five alpine disciplines. Millie is one of the most decorated Paralympic skiers of the past decade, and is a four-time Paralympic medalist and two-time World Champion. When she was young, she lost most of her vision due to eye infections and now competes as a low vision para-sport athlete. She currently skis with the assistance of a guide, Brett Wild, who communicates through Bluetooth technology, giving updates on slope conditions. Throughout her career, Millie has suffered multiple concussions and injuries. She continues to suffer from persisting symptoms as a result of her concussions. This interview highlights her experiences with concussions as a para-sport athlete.

Interview with Paralympic Skier Millie Knight

Persisting Symptoms for Individuals with Pre-Existing Disability

Persisting symptoms are common after a concussion, especially for athletes with a pre-existing disability. Future studies need to examine if certain disabilities put individuals at an increased risk for persisting symptoms, or if certain disabilities may put individuals at risk for a longer recovery trajectory. According to the 6th Concussion in Sport Group Consensus Statement, if symptoms persist beyond 4 weeks, further treatment should be specific to an athlete’s individual symptoms. Navigating persisting symptoms for disabled athletes is particularly challenging; persisting concussion symptoms may be hard to decipher from pre-existing symptoms, certain therapeutic interventions may not be accessible to certain disabled athletes, and persisting symptoms may reduce everyday functioning. Early aerobic exercise that does not provoke symptoms by more than 1-2 points out of 10 has been shown to be helpful in concussion recovery after relative rest within the first two days of injury. Safely exercising in a calming environment specific to the athlete’s preference may be helpful for recovery. Persisting symptoms may impact concentration for athletes with low vision, thus making daily activities and the ability to rest and move more challenging.

Common persisting concussion symptoms include: headache, fatigue, cognitive symptoms, emotional dysregulation, sleep problems, neck pain, and dizziness.

Learn more about persisting symptoms on our page here.

Treatment options may include seeking support from: hospital-based outpatient rehabilitation centers, concussion clinics, mental health professionals, physical therapists, and vision therapists. Furthermore, certain therapies such as graduated exercise therapy, vestibular therapy, hormonal therapy, acupuncture, and others may be beneficial.

To find out more about these therapies, visit our concussion treatments page here.

Mental Health and Pre-Existing Disability

Research in the Disability and Health Journal found that people with disabilities have higher rates of chronic pain and emotional distress. Furthermore, according to a press release by the Cleveland Clinic, those struggling with anxiety and depression also have a higher likelihood of developing post-concussion syndrome, including prolonged persistent symptoms and a longer recovery time. While the press release uses the terminology post-concussion syndrome, the recent 6th consensus statement on concussion in sport advocates for the use of the term ‘persisting symptoms after concussion,’ which more accurately reflects the injury. This highlights the importance of mental health support in the treatment of concussion and ongoing symptoms for athletes with a pre-existing disability.

The athlete psychological strain questionnaire (APSQ), along with other questionnaires included in the SMHAT-1, helps to identify athletes at risk for mental health struggles.

Female Paralympic athletes tend to score higher, indicating more psychological symptoms.

Winter athletes also tend to score higher on these questionnaires when compared to summer athletes.

Check out our pages on Mental Health, Mental Health Among High Schoolers, The Invisible Injury, and Emotional Wellness for more information & resources to assist in recovery.

Disability Stigma and Navigating Healthcare

Stigma is a negative set of beliefs associated with a subset of individuals with certain characteristics. More specifically, according to a press release by the University of Washington, disability stigma can manifest as discrimination, condescension, stereotyping, social avoidance, negative internalization, and hate crimes or violence.

One example of disability stigma that can impact treatment is the cost of healthcare in the United States. According to a press release by the CDC, people with disabilities are more likely to have a total salary of less than $15,000 compared to people without disabilities (22.3% compared to 7.3%). This may contribute to the bigger picture of individuals with disabilities who downplay or ignore their symptoms. Another reason for downplaying symptoms includes “self-gaslighting,” where someone who may be in chronic pain may try to convince themselves that their symptoms aren’t so bad or they can handle it. This negative internalization and denial can manifest as a result of general disability stigma. Disability stigma may interfere with proper diagnosis and assessment of concussion. Below are some tips and tricks to help successfully navigate the healthcare process with an underlying disability.

Getting seen for a possible concussion if you have an underlying disability: How to navigate the healthcare process with an underlying disability successfully.

Healthcare professionals treating patients with underlying disabilities: Disability stigma may interfere with proper diagnosis and assessment of concussion. Below are ways that could help avoid disability stigma:

Blind or Low Vision Individuals

Blind or low vision individuals face a unique challenge to concussion diagnosis and treatment. According to a study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, English blind footballers have a greater risk of sustaining a concussion compared to able-bodied footballers. Many participants could not even quantify how many concussions they had sustained, and “they perceived the diagnosis and experience of a concussion to be different for a person without vision.” Many of these athletes are both at higher risk and have more difficulty recognizing and receiving diagnoses. This concerning finding raises the question of how many concussions go unnoticed or untreated in the blind or low vision community. Below is a section dedicated to helping blind or low vision individuals navigate proper concussion diagnosis and care.

Concussion Education

Extra steps should be taken to ensure information on concussion education is easily accessible for blind or low vision individuals. To make it more accessible for blind/low vision athletes, providing concussion information through audio or braille may be necessary. Furthermore, athletes with intellectual impairments may need extra assistance for information comprehension.

Adaptations to Sports Equipment

Adaptations to equipment for blind and low vision athletes may include softer/low bounce balls or balls with beepers attached. For athletes who play blind football, increasing verbal communication and signals can reduce the chances of on-field collision, considering all athletes in blind football are required to wear blindfolds to account for athletes who may have partial vision. In addition, blind skiers use the verbal assistance of guides to help navigate the slopes.

Concussion Assessment

Below are assessment options to help properly diagnose a concussion specific to blind or low vision athletes. This may also be helpful as a resource for the general population who are blind or low vision. These options are adapted from a resource from the Concussion Awareness Training Tool website.

Orientation and mobility assessment: Assessing an athlete’s spatial awareness and ability to orient themselves in an environment.

Functional vision assessment: During a vision assessment for blind or low vision athletes, it’s imperative to ask athletes if their ability to do tasks feels harder than it usually does, or if they notice a change in their vision.

Vestibular testing: Vestibular testing assesses an athlete’s balance with a variety of tools or movements. For example, a provider may have an athlete balance on a foam pad or stand up straight with their hands out in front of them.

It is critical to ask individuals if any of these tasks feels worse or harder than it usually does, or is more difficult than the baseline testing.

Persisting Symptoms

Managing persisting symptoms in regard to individuals who are blind or low vision should be individualized and adapted to fit chronic conditions and pain.

According to a study outlining the management of persistent symptoms for athletes with visual impairments, “Athletes with VI [visual impairment] may have reduced static balance, and elements of vestibular rehabilitation and training may require adaptation; individuals with reduced visual performance may have baseline chronic neck pain and thus elements of cervical spine/neck therapy may require adaptation.”

Navigating Disability Stigma

In terms of the blind and low vision community, barriers in the healthcare system include the use of print material and lack of Braille or screen-reader friendly material for those with screen readers. Furthermore, those who are not able to drive due to visual impairments may find it difficult to get to their appointments in the first place, especially if there is a lack of convenient public transportation.

Some general tips for disability etiquette towards individuals who are blind or low vision adopted from a Disability: IN resource include:

Identify yourself when entering a conversation and announce when you leave

When serving as a sighted guide, offer your arm or shoulder rather than grabbing or pushing the individual

Describe the setting, environment, written material, and obstacles when serving as a guide

It is ok to use normal language such as “see you later” to someone who is blind or low vision; using ordinary expressions demonstrates that you see them as full members of the community

Resist the temptation to pet service animals or talk to guide.

Related Blog Posts

Acknowledgments

Due to the limited research on concussions and athletes with pre-existing disability, this page could not have been possible without the help of some very special people.

We would like to thank Dr. Osman Ahmed for his encouraging and thoughtful mentorship throughout this project, as well as his team’s foundational and informative work on the topic of concussions in para-sport athletes.

We would like to thank Millie Knight for her powerful talk with us on her personal experiences as a Paralympic skier having battled concussions.

We would like to also thank Angela Romeo for her guidance and first-hand experience in disability advocacy work and for sharing her story with us.

We would like to thank Augden Hayes for helping us brainstorm and edit the structure and language of this page.

Finally, we would like to acknowledge and thank Conor Gormally, Malayka Gormally, Hannah Nash, and Kira Kunzman for their unwavering help and support throughout the process of creating this page.

We want to emphasize that this page is just a starting point for a larger conversation about disability and concussions. We welcome any suggestions for improving this resource and hope to include more research as it comes out.

Dr. Mac Donald et al. conducted a 10-year prospective study of veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan to determine the trajectory of disability within this population and identify which subset of the population is most at risk. Their study demonstrated that veterans who sustained a concussion in combat had “very high odds of poor long-term outcome trajectory.”