Concussion in Youth Sports

Concussions can happen anywhere and at any time. However, sports settings present an increased risk for concussions. Whether you pick up a sport for the first time or have played it your whole life, understanding concussions is essential for your health and safety. Concussion education is the first step in changing the culture surrounding concussions in sports and providing a safe environment for every player.

Sports-related concussions can happen at any level; this page provides general information about concussions as well as concussion issues specific to sports. We also have an in-depth section on concussions in high school athletes. In the future, we will add sections for additional age groups.

Table of Contents

Persistent Post-Concussive Symptoms | Football | Ice Hockey | Soccer | Cheerleading

Concussion Education

We recommend that athletes, coaches, parents, and guardians do some concussion education at the start of the season. Interactive concussion education helps with information retention and understanding the consequences of concussion-related decisions. We recommend online concussion education using our webinar, CATT, and Teachaids.

Our webinar discusses the patient-centered approach to concussion care for both physicians and non-physicians. It includes essential educational material for patients, physicians, guardians, and coaches. After viewing, Grassroots Rugby coach Graham Oliver noted that his “understanding of concussion and its immediate and long-term symptoms was much clearer.” We also have a blog post if you want to learn more about the webinar.

Concussion Awareness Training Tool (CATT) is a joint project of the BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit, BC Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. CATT has an E-Learning Concussion Training Course for Youth and an E-learning Concussion Training Course for Athletes. We highly recommend the CATT educational courses.

The CrashCourse Concussion Education by Teachaids.org, affiliated with Stanford University, has two interactive educational videos that are helpful for athletes, parents, and coaches. The novel interactive elements of these videos make them worthwhile.

The first video, CrashCourse, teaches interactive concussion lessons using a football team environment. While this perspective provides a clear run-down of sport-related concussion recovery and prevention processes, the first video focuses on football in a manner that may not be appealing to all audiences.

The second video, Crash Course | Brain Fly Through, features interactive lessons from the perspective of a female mountain biking athlete. Although a worthwhile course, especially because of the female perspective, we believe the Brain Fly Through has some inaccuracies.

The video says that the majority of concussion symptoms will resolve in children in approximately ten days. PedsConcussion states, “Children typically recover in 1-4 weeks, but some children/adolescents will have symptoms at one month and beyond and need to be monitored/seek additional care. Females aged 13-18 have an increased risk of prolonged recovery.” New research suggests that even for adults, “Normal concussion recovery could take up to one month.” Prolonged recovery due to certain pre- and post-injury risk factors is also an issue.

Kate Courtney mentioned that she was symptom-free and back to competing within seven days of sustaining her second concussion. This is not the typical timeline for recovery and for returning to competition. Consult with your medical provider, and do not return to sports until you are officially cleared by a medical professional.

Benefits of Youth Sports

This image summarizes the benefits of youth sport participation. Image created by Catie Marvin (Winter 2022 Concussion Alliance Intern).

Considering these benefits, it’s important to understand the risk factors associated with high school sports and the different preventive measures you can take to lower your risk of concussions.

While youth sports have dangers, it’s essential to recognize the many potential benefits of sports participation.

Educational benefits associated with participation in youth sports include higher levels of academic achievement, improved teamwork, time management, and leadership skills. High school athletes are also more likely to attend and graduate from a four-year college.

Emotional and social benefits include lower amounts of anxiety, depression, and stress, as well as greater self-esteem and confidence.

Physical benefits such as improved bone health and increased cardiovascular and muscular fitness are also associated with participation in sports. Adolescents who participate in sports are more likely to continue to be physically active later in life.

Mythbusting

There is a lot of misunderstanding regarding the causes and the proper care of concussions. Unfortunately, these misunderstandings can sometimes negatively impact the recovery process. Hopefully, a better understanding of the truths of concussions may lead to a more efficient and successful recovery.

This image non-exhaustively describes common myths surrounding concussions. Image created by Lexi Kingma (Winter 2022 Concussion Alliance Extern).

Signs and Symptoms

This image depicts standard and red flag concussion symptoms. Red flag symptoms require immediate medical attention: call 911 or get to an emergency room if these symptoms are observed. Image created by Catie Marvin (Winter 2022 Concussion Alliance Intern).

While signs and symptoms will vary between concussion patients, some symptoms require immediate medical attention. These symptoms are called danger signs or red flag symptoms. If you or anyone you know has one of the following signs or symptoms, call 911 or immediately go to the emergency department.

Red Flag Symptoms

One pupil is larger than the other

Extreme drowsiness or will not wake up

A headache that gets worse and does not go away

Slurred speech, weakness, numbness, or decreased coordination

Repeated vomiting or nausea, convulsions or seizures

Unusual behavior, increased confusion, restlessness, or agitation

Loss of consciousness (even if brief)

Deteriorating mental state

Concussion signs and symptoms may vary from person to person. People around the concussed person observe signs of a concussion. The concussed person reports symptoms. Signs and symptoms generally appear right after the injury, but some can take hours or days to develop.

Common Signs Observed:

Trouble remembering events from before or after the injury

Appearing dazed or stunned

Forgetting or being confused by instructions

Being unsure of the game, score, or opponent

Moving clumsily

Answering questions slowly

Changes in behavior, mood, or personality

Vomiting (repeated vomiting is a red flag)

Common Symptoms Reported

Headaches and “pressure” in the head

Nausea

Balance problems or dizziness

Double or blurry vision

Noise and light sensitivity

Feeling sluggish or foggy

Confusion

Memory and concentration problems

“Just not feeling right” or “feeling down”

New onset of rapid and unusually intense changes in mood

Subconcussive Hits

Subconcussive hits are impacts sustained below the threshold required to cause a concussion and don’t present symptoms. These impacts may appear inconsequential, but an accumulation of subconcussive hits may, just like a concussion, contribute to microstructural damage in the brain, memory problems, and depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Multiple Concussions

While research findings are mixed, there is some evidence that suggests there are consequences of multiple concussions. Athletes with a history of concussions may have more severe subsequent concussions and may take longer to recover. Some athletes with multiple concussions show neurocognitive impairments in memory and processing speed. Among athletes that sustained 3-5 concussions, injury-attributed changes in their default mode network (DMN) decreased cognitive performance. Furthermore, a recent study found a correlation between athletes with a history of concussion and changes in brain microstructures and blood flow.

Second Impact Syndrome

Second impact syndrome (SIS) is a condition in which an individual sustains a second brain injury during a window of vulnerability following the initial brain injury. This condition is relatively rare, but athletes who sustain a concussion and return to their sport too soon may be at higher risk, as are athletes who remain in the game after a concussion. The syndrome is often fatal but can also lead to severe cognitive disabilities.

Impact of Sex

The following section uses the binary language of gender & sex due to the prominence of research with binary experimental design. For additional information, see our resource page, Concussion in Women and Girls.

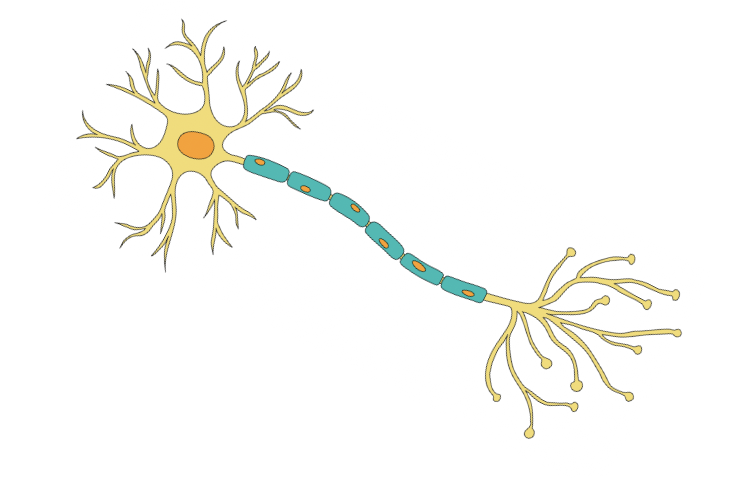

Females and males experience concussions differently. The majority of research indicates females are at higher risk for concussion. Biological and social differences help explain the gap in concussion risk and recovery between females and males. These include, in women, less average muscle mass, fewer stabilizing structures in brain axons, menstrual cycles, hormonal fluctuations, and cultural influences. As a result, if a female is returned to activity too early in the graduated recovery process, they are 1.5 times more likely to experience a relapse of symptoms than males.

Biological Differences

Neck muscles are vital in stabilizing and preventing the head from extreme, abrupt movement. On average, men have more muscle mass around the neck and shoulders than women, rendering them less susceptible to concussive forces

The female axon, the information highway in brain cells, has fewer microtubules. Microtubules are strong structures in the axon that provide shape and support. Additionally, female axons are observably more flexible and thin than male axons. With the same force, the average female brain cell is at higher risk of damage than the male.

Young females in the luteal period, the second half of their menstrual cycle, experience a drop in the hormone progesterone. The hormonal change has been linked to worse post-concussive symptoms in females than males in a similar situation. Certain studies demonstrate an irregular menstrual cycle 3-4 months after injury in some females.

Gendered Social Differences

From a cultural perspective, researchers argue men and boys are more involved in and encouraged to endure high-collision sports than women and girls. As a result, boys may learn to avoid and take collisions using injury-preventing techniques from a young age.

Other studies indicate women and girls are less likely to be removed from play after injury and less likely to seek care promptly. Unfortunately, in the existing concussion research and literature, females are underrepresented.

Risk of Youth Sports

Concussions can happen anywhere and at any time. However, around 3.8 million sports-related concussions (SRC) occur each year in the United States. Football, ice hockey, soccer, and cheerleading have higher rates of concussion when compared to other high school sports.

Persistent Post-Concussive Symptoms

With the popularity of youth athletics, it is critical to address the higher risk of concussion and post-concussive symptoms in young athletes, particularly high schoolers. Most adolescents will fully recover from a concussion. However, a percentage of concussion patients experience what is variously called persistent post-concussion symptoms, prolonged symptoms, or post-concussion syndrome (PCS). “A wide range of reported incidence in the literature is reported from 30 to 80 percent of patients with mild to moderate TBI experiencing signs and symptoms of PCS.” For more information, see our page, Prolonged Symptoms of Concussions.

Football

Football is one of the most popular sports in America. However, concern has been rising recently about the safety of this sport, especially in terms of concussions. This concern is appropriate because football had the highest concussion rate compared to 20 other high school sports. Another study shows that the risk of developing Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) doubles with every 2.6 years spent playing football. All levels, including youth football, were included in the data. It is important to consider that some research indicates that the earlier your child enters a contact sport, the higher their risk for cognitive issues or even neurodegenerative disease later in life. However, this research is still in relatively early stages, and many factors beyond concussive and subconcussive may affect risk levels. Our synopsis of this research can be found on our blog here.

The largest proportion of concussions occurs in linebackers, running backs, and offensive linemen. Other data suggests that while linebackers experience the largest proportion of head impacts, running backs and defensive backs experience the highest acceleration head impacts. Teams with a “run-first” offense recorded more head impacts than teams with a “pass-first” offense. However, teams with a “pass-first” offense had higher-severity head impacts.

Recent research shows that a little more than half of high school football concussions occur during practices. It can be difficult to control the intensity or conditions of games, but there are ways to mitigate some of the dangers associated with football practices. A recent meta-analysis shows that contact training and contact restriction may help reduce concussion rates at practices. This can be done by limiting the number of days of full-contact practices, minutes spent on full-contact each practice, and the intensity of drills. Limiting live drills may help reduce head impacts in practice. In Wisconsin, the prevalence of practice-related concussions decreased by 57% when full-contact practices were limited. Heads Up Football, an intervention focused on educating coaches on concussions and contact training, has been shown to reduce the rate of concussions by 32% and head impacts by 38% in high school football players.

This image is an infographic with tips for getting the right fit with a football helmet. It was made by the National Athletic Trainer’s Association.

A common misconception is that helmets protect players from concussions. Concussions are caused by force to the head or body that causes the brain to bounce around or twist in the skull. While helmets may aid in preventing injuries such as skull fractures, helmets do not protect the brain from hitting the inside of the skull. Poor helmet fit is associated with increased concussion symptoms and symptom duration. Check out this factsheet from the CDC that gives tips on choosing the right helmet.

Looking for more resources? Heads Up Football is a program developed by USA Football to increase safety in football. USA Football’s Youth System is a program to teach coaches about safe contact skills. Here is a practice guideline for youth football.

This page focuses on high school football. For more information about youth football, check out our blog post and the Concussion Legacy Foundation’s page on their Flag Football Under 14 campaign.

Ice Hockey

Ice hockey is yet another sport where players are at higher risk of sustaining concussions. Younger players who haven’t completed physical maturation (puberty) may experience more severe symptoms and recovery. The physicality of hockey requires a 40% longer concussion recovery time for younger (aged 13-18), less physically developed players. Scientists concerned with this age discrepancy recommend that young athletes not “play up” or don’t play at a level dominated by older, more physically mature players.

In one particular season of elite youth hockey in Alberta, Canada, 18 concussions occurred for every 100 players. While the preventative measures and individual recovery processes for each reported concussion are unclear, 74% of concussed players required more than 10 days to recover, and 20% required more than 30 days. International guidelines state that the average recovery time for children is 4 weeks. Recent research indicates that normal recovery time for adults is also one month.

Many concussions occur due to body checking, a maneuver where one uses their upper body to separate another player from the puck. Recent research indicates that among 15-17 year-olds, players could avoid 51% of concussions with the removal of body checking. Similar to other collision sports, there is a proven correlation between more years of playing ice hockey and a higher risk of developing chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE.

Parachute’s concussion program provides an informative, interactive resource for hockey players of all ages.

Soccer

An essential part of recovery is a support system. Returning to school can be challenging and requires lots of communication and teamwork. We recommend that each student form a “Concussion Management Team.” This team should include but is not limited to the student, parents or guardians, coaches, a healthcare professional, school administrator, school nurse, and teachers.

Contrary to popular belief, concussion patients should not lay in a dark room until symptoms resolve. There is evidence that prolonged rest may increase symptoms and recovery time. Instead, a short amount of rest (24-48 hours) is recommended, followed by a gradual return to activities.

All soccer players are in danger of concussion due to heading and player collisions. Players heading the ball (when players jump and drive the ball forward with their heads) risk collision with another player in the air or sustaining a hit from the ball, transmitting force across their brain. Players may also run into one another during general play, leading to multiple injuries, including subconcussive impacts and concussions.

In one study, players performed an average of 125 headers over two weeks and were three times more likely to develop a concussion than those who rarely headed in that same period. Despite the apparent risks of heading, studies have demonstrated that soccer players sustain concussions more frequently after player-player collision than repeated head-ball contact. In both boys' and girls' high school soccer, defensive concussions occurred about twice as often as heading-related concussions.

As of January 2016, US soccer implemented an initiative to reduce the number of concussions in youth and adolescent play. The initiative prohibits heading in U11 (age 11) groups and younger and discourages the maneuver in U12/13 groups. Nonetheless, there are no national restrictions in place for high school athletes at higher risk of suffering more intense and prolonged post-concussive symptoms.

US Soccer's CDC resources have helpful fact sheets and training programs.

Cheerleading

Not all high schools consider cheerleading a sport because of the lack of “player-to-player” competition. However, there are significant risks associated with cheerleading. The complex moves and routines cheerleaders practice and perform put them at high risk for injuries, especially concussions.

A study published in 2021 found that around one-third of all patients accepted into the ER for sports-related concussions (SRC) or closed head injuries (CHI) were females aged 14-18. Cheerleaders accounted for around 10 percent of these injuries. A 2018 study showed that cheerleading had surpassed football in concussion risk rates.

In recent years, the rate of overall cheer-related injuries has decreased while the rate of concussions has increased. Concussions are the most common head injury in cheerleading, and 96% come from stunt-related incidents. Most concussions sustained by bases (an athlete that holds up another athlete in the air during a stunt) result from contact with another athlete. Whereas most concussions sustained by flyers (athlete that is in the air during a stunt) result from contact with the ground.

Recent research shows concussions are more likely to happen during practices than in competitions. Cheerleading teams sometimes practice in less-than-ideal conditions. Some teams practice in hallways or on asphalt. They also may have less medical oversight and coaching support than other high school sports. This statistic could also be explained by the significantly higher proportion of time spent in practice rather than in competition.

Possible ways to decrease the risk of concussion in cheerleading are the regulation of stunts, ensuring the safety of equipment and practice facilities, providing more medical resources, and the official recognition of cheerleading as a sport. If more schools were to recognize cheerleading as a sport, more resources could be given to teams, such as mandatory concussion education and baseline testing.

Looking for more resources? Here is a concussion management plan made by USA Cheer. Check out this personal story of a high school cheerleader posted by the CDC. Here is a page published by USA Cheer with links to educational resources.

Return to Learn

This page focuses on concussions in sports, but many athletes are also students. Returning to school is an essential part of concussion recovery for children and adolescents.

Recovery from a concussion can be difficult, and returning to school may feel daunting. While symptoms last, a concussion may inhibit a student’s ability to participate, learn, and perform well in school. A gradual step-by-step plan may make the return feel more manageable. This section will cover returning to school or “return to learn” (RTL).

This image depicts an example of a concussion management team. Image created by Catie Marvin (Winter 2022 Concussion Alliance Intern).

We want to emphasize two important principles from PedsConcussion, the Living Guideline for Pediatric Concussion Care.

“The child/adolescent should return to their school environment as soon as they are able to tolerate engaging in cognitive activities without exacerbating their symptoms, even if they are still experiencing symptoms.”

“Complete absence from the school environment for more than one week is generally not recommended. Children/adolescents should receive temporary academic accommodations (such as modifications to schedule, classroom environment, and workload) to support a return to the school environment in some capacity as soon as possible.”

About Return to Learn Stages

Many RTL plans and guidelines exist. Concussion Alliance has developed a series of steps for returning to school adapted from, Parachute’s Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport, Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport, CATT Return To School, McMasterU’s CanChild Return to School Guideline, and Ophea’s Ontario Physical Education Safety Guidelines.

Each stage increases cognitive workload while working to minimize symptoms. The first stage lasts 24-48 hours. The duration of the rest of the stages will vary depending on the individual student’s symptoms. Still, each stage should last at least 24 hours. The student can progress to the next stage when they have completed the activities in the previous stage without new or worsening symptoms. Symptoms do not need to disappear entirely for a student to move to the next stage. If symptoms worsen, the student can remain at the same stage for an additional 24 hours or return to the previous stage; this process should be repeated until the student does not experience any new or worsening symptoms at their current stage. Watch out for any red flag symptoms and get immediate medical attention if one or more is present.

Return to Learn Stages

Stage 0

Complete Cognitive and Physical Rest (24-48 hours): Minimize screen time, TV, reading, bright lights, and loud noises. Completely avoid school attendance, work, sports, and physical exertion. You can do low cognition activities such as crafts or short board games as tolerated. Move to the next stage when symptoms improve or after 24-48 hours of rest.

Stage 1

Light Cognitive Activity: Activities such as peer contact, light reading, crafts, short amounts of TV, and light aerobic exercises such as short walks are ok in this stage as tolerated. Continue to avoid school attendance, work, sports, and physical exertion. Move to the next stage when 30 minutes of light cognitive activity is tolerated at home.

Stage 2

School-Type Work at Home: Introduce school-like activities, such as readings or light assignments, in 30-minute chunks. Continue to avoid school attendance, work, sports, and physical exertion. Move to the next stage when 60 minutes of cognitive activity is tolerated.

Stage 3a

Part-Time School With a Light Load and Accommodations: In this stage, school attendance is reintroduced. Start with half-days at school 1-2 times a week. When at school, 120-minute chunks of cognitive activity are allowed, taking breaks when necessary. Light physical activity is recommended as well. Avoid music and PE class. Tests, exams, quizzes, and homework are not recommended during this stage. Still avoid sports and intense physical activity. Move to the next stage when 120 minutes of school work 1-2 times a week is tolerated.

Stage 3b

Part-Time School With a Moderate Load and Accommodations: In this stage, increase school attendance to 3-5 times a week. School attendance is ok for 4-5 hours a day, taking breaks when needed. Up to 30 minutes of homework a day is allowed. Limited testing is allowed at this stage, but communicate with your teachers and doctor about accommodations. Begin to decrease learning accommodations in this phase. Avoid PE classes, sports, intense physical exertion, and standardized exams. Move onto the next stage, when 4-5 hours of school attendance is tolerated in chunks for 2-4 days a week.

Stage 4a

Nearly Normal Workload: In this stage, the student is back to nearly normal cognitive activities. You can complete routine school work as tolerated. Homework is ok for up to 60 minutes a day. The student should have minimal learning accommodations at this time. Continue to avoid PE classes, standardized exams, and full participation in sports. Move to the next stage when a full-time academic load is tolerated without worsening symptoms.

Stage 4b

Full-Time School With No Accommodations: The student can return to normal cognitive activities, routine school work, full workload, and no learning accommodations. This signals the end of the return to learn process. The student may return to sports when cleared by a medical professional.

This image depicts the 7 stages of Return to Learn. This image is from Parachute’s Concussion Series .

While returning to school is an essential part of concussion recovery, the school environment can also aggravate symptoms. Check out this resource from Peds Concussions (an evidence-based living guideline for pediatric concussion care) about adjusting different parts of the student’s schedule and environment to alleviate symptoms.

Premature RTL is associated with a higher chance of a relapse of concussion symptoms. In recent years premature return to play (RTP) has significantly decreased, but premature RTL has not. This indicates a need for greater awareness and implementation of RTL plans.

Returning to school and sports can be performed simultaneously. However, it is recommended that the student returns to school full-time without accommodations before fully returning to sports.

Many students will only need slight informal academic adjustments and support while they recover from a concussion. However, some kids may have significant initial or persisting symptoms requiring more formal support. We have compiled some resources below:

PedsConcussion: Return to School

Concussion Alliance: Concussion Management

Children’s Hospital of Chicago: Return to Learn after a Concussion: A Guide for Teachers and School Professionals

Return to Play

The athlete MUST complete the return-to-learn (RTL) plan before the return-to-play (RTP) plan. Note: this does not mean that the athlete must abstain from physical activity until they complete the RTL plan. Gradually increased activity is an important part of early concussion recovery; see our resource page on Graduated Exercise Therapy and our blog post Aerobic Exercise as Therapy. Athletes should refrain from continuing to any contact-risk components of RTP plans until they complete RTL.

The most effective return-to-learn and return-to-play strategies require an interdisciplinary, collaborative team. Cognitive and physical rest are integral to recovery, but completing a gradual return-to-play strategy allows the player to reacclimate their body slowly to the strains of exercise.

If, at any point in the return-to-play process, the athlete experiences aggravated symptoms, they should alert their clinician and return to the last non-symptom-inducing stage. If the athlete experiences any red flag symptoms, immediately seek emergency care. After a certified clinician has diagnosed the player with a concussion, they should follow the following graduated recovery process:

Return to Play Stages

Stage 0

Complete cognitive and physical rest (24-48 hours): The athlete should rest for a maximum of 1-2 days, based on the clinician's recommendations. Any more time may lead to prolonged recovery and exacerbated symptoms. To reduce cognitive strain, avoid certain activities such as extended screen time, high light exposure, and physical exertion.

Stage 1

Light physical activity: After the initial 24-48 hours of rest, the athlete should be able to move around their house such that they do not sweat or raise their heart rate. This may include walking leisurely around the house and performing simple chores. There should be no sport-related activity yet.

At the beginning of recovery, keeping heart and breathing rates low is essential to avoid aggravating symptoms.

Stage 2a

Beginning aerobic exercise: As long as symptoms allow, the next step for an athlete is to begin light aerobic exercise. In addition to building on the activities from previous stages of recovery, the athlete may now integrate short periods of light activity, such as walking for 10-15 minutes. They should still avoid raising their heart rate and avoid sporting activities.

Stage 2b

Continuing aerobic exercise: At this point, the athlete may raise their heart rate and breathing but still be able to maintain a conversation. Periods of aerobic exercise may last as long as 20-30 minutes. The athlete should still avoid sporting activity as well as resistance training. Implementing weights or resistance bands this early may prevent the nervous system from adequately regulating blood flow to the brain, worsening symptoms such as dizziness, trouble breathing, or a headache.

Stage 3

Sport-specific individual movement: As symptoms improve and the player becomes more comfortable with aerobic exercise, the athlete may begin to implement sport-specific drills with the advice of the clinician, therapist, or coach. There should be absolutely no risk of head or body contact during these drills. Any additional impacts may be highly detrimental to recovery and lead to the second-impact syndrome.

Stage 4

Non-contact exercises: The athlete may return to more complex non-contact exercises and graduated resistance training with the clinician or trainer's approval. The athlete should be targeting sport-specific skills and coordination at this stage. This should still occur in an environment with no risk of head impact or abrupt body movement that could exacerbate the injury.

In order to continue to the next stages of the return-to-play process, the athlete must have finished the return-to-learn process, show no symptoms, and be cleared by a medical professional.

Stage 5

Full-contact practice: To graduate to full-contact practice, the athlete must pass a complete cognitive and physical evaluation from their clinician.

Stage 6

Return to game: Despite having medical clearance, it is crucial for the athlete to continuously scan for any lingering symptoms from their injury and immediately report it to their coach, trainer, or clinician if they come across any. The athlete should strictly follow safe and preventative guidelines in further play to avoid re-injury.

PedsConcussion recently updated their guidelines for "patients who are active" and those who are "highly-active or competitive athletes, those who are not tolerating a graduated return to physical activity, or those who are slow to recover." The new guidelines recommend these groups be referred "to a medically supervised interdisciplinary team with the ability to individually assess sub-symptom threshold aerobic exercise tolerance and to prescribe aerobic exercise treatment. This exercise tolerance assessment can be as early as 48 hours following acute injury."

Remember, several factors may contribute to the worsening of symptoms and delayed recovery:

Neglecting the advice of clinicians, therapists, trainers, or coaches

Adding resistance training too early

Resting longer than 2 or 3 days

History of concussion or sub-concussions

Delayed diagnosis

The recovery process may feel overwhelming. With the right recovery team and support structures, a graduated return-to-play can significantly improve symptoms and streamline healing. Finding a recovery team may be difficult, but Concussion Alliance has an easily navigable page to search for providers. The Concussion Awareness Training Tool provides many helpful resources to break down recovery into digestible parts. The International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy published an article delineating sport-specific exercises for a gradual recovery. If you want to dive deeper into the specifics of each stage, Boston Children's Hospital has an intensive progression of return-to-sport diagram.

Preventative Measures

Contrary to popular belief, concussions are partially preventable when well-informed. The following behaviors help avoid concussions in sports:

Reducing aggressive movements/maneuvers

Adherence to concussion protocols

Educating oneself and reducing stigma among athletes, parents, coaches, and doctors

Prioritizing health (mental and physical) over playtime

At athletic events, on-the-go protocol sheets provide basic concussion information. Image from Parachute.

Several studies have determined that removing aggressive and collision-prone activity across multiple sports leads to decreased rates of concussions. For example, limiting heading in youth soccer, body-checking in hockey, and particular types of tackling in football results in significantly lower collision-related concussions.

Each team, school, or club should have a concussion protocol ready to implement. It should include a minimum of a concussion definition, basic education, removal from activity criteria, an evaluation process, and return to learn and return to play procedures.

These measures are significantly less helpful if one is unaware of the risks, causes, symptoms, and treatments of concussions. Education on concussions in sports across all ages may improve awareness and encourage athletes to prioritize their health over the benefits of playing their sport. There are many accessible programs, such as Parachute’s concussion education app.

There are a few methods of diagnosing concussions and determining the appropriate next steps. These include side-line evaluation, concussion screening, and post-injury testing. Side-line evaluations are critical the moment after possible injury. The player must pass a symptom and cognitive assessment conducted by the athletic trainer or another certified person before returning to play. Away from play, clinicians may implement a concussion screening post-injury, including a physical and cognitive exam.

While the primary goal is to avoid concussions altogether, there are additional methods for preventing further injury.

Players

Recovering from a concussion can be challenging. Especially when managing school, sports, and social life. Sustaining a concussion often means taking breaks from school, sports, and some of your usual activities with friends. This can be very difficult and frustrating, and you may feel like you’re missing out on things or falling behind. Concussions are associated with an increased risk of mental health issues, and recovery can be very isolating. As many as one-third of youth with concussions reported increased levels of anxiety and depression after their injury. It is important to be kind to yourself and let your body heal. Be honest with yourself, your parents, coaches, teachers, friends, and doctors about your symptoms and recovery process.

Concussions do affect not only the person with the injury but also those around them. Your friends and teammates may suffer from concussions. It may be confusing and frustrating to watch your friends recover from a concussion or to see your teammates unable to practice or play. It’s important to remember that each person experiences concussions differently, and there is no set recovery timeline. Try to be patient and flexible with your friends, classmates, and teammates. People with concussions may be more irritable or experience mood swings, which can be challenging to be around. Remember that this is likely a result of the concussion, and try not to take it personally.

Take time to check in on your friends and do activities with them that will not worsen their symptoms:

Cooking or baking

Walks

Yoga

Coloring or painting

Board games

Talks

It may help to hear other people’s stories or do your own research to understand your injury and the recovery process. Below we’ve compiled some resources you may find helpful.

Concussion Alliance: Mental Health, The Invisible Injury, Overview of Self-Care, and Social Support

Crash Course: Concussion Story Wall

Headway Foundation: Effects of Brain Injury

Brain Injury Canada: Mental Health of Brain Injury Survivors

CATT Online: CATT Youth Training Course

Northwestern University: How Counseling Can Help After a Concussion

Coaches

Young athletes may try to seem “tough” by hiding or downplaying their injuries. Coaches play a crucial role in setting the tone and building a team environment that puts safety first. As many as 7 in 10 young athletes with a possible concussion report playing with concussion symptoms. Out of those, 4 in 10 said their coaches were unaware of their potential concussion. Here are a few tips for coaches to educate their athletes to promote open and honest communication about head injuries on the field.

Learn the Signs and Symptoms

Learn and educate your players on the signs and symptoms of concussions. Signs and symptoms can appear right after the injury but sometimes take hours or days to develop. It’s important to check in with your athlete directly after injury and continue monitoring for symptoms afterward. Also, look out for red flag symptoms, call 911 or get your player to an emergency department if any of these occur. Below are some resources for concussion education.

CATT: Parent or Caregiver Concussion E-Learning Course

Get a Heads Up: Concussion Signs & Symptoms

Understand the Effects

Concussions are serious injuries and should not be taken lightly. Explain the short-term and long-term effects of concussions. Continuing to participate in sports with a concussion can worsen symptoms and delay recovery. Between 30 and 80 percent of patients with mild to moderate traumatic brain injuries experience signs and symptoms of post-concussion syndrome. Knowing the risks of concussions, seeking medical care, and avoiding reinjury during recovery are some of the most important things an athlete can do for their long-term health.

Create a Safe Environment

Sports can be a safe and fun space for kids to exercise and socialize. By creating a space that puts safety first, you can lower the risk of concussions and other serious injuries.

If players report concussion symptoms to you, provide positive reinforcement and take their concerns seriously.

Encourage proper concussion reporting without worrying about losing their team position, looking “weak,” or letting their teammates down.

Do not let your players return to play without proper medical clearance.

Encourage their teammates to support each other when they are sitting out.

Encourage technique over physicality and praise player behavior that keeps the team and the opponents safe

Enforce the Rules

Despite attempts to educate your players and prevent concussions, accidents happen, and so will concussions. Enforcing the rules for fair and safe play may help decrease the risk of injury. Avoid unnecessarily rough plays and contact. Around 25% of concussions in high school athletes result from aggressive or illegal play. For sports that require contact, such as football, teach the correct form and discourage illegal plays and poor sportsmanship.

Have a Concussion Action Plan

Create a plan for when concussions occur ahead of time and communicate the steps with your players and their parents. Check out the CDC’s resources here and here, as well as our recommendations below:

Immediately remove the athlete from play.

Have the athlete evaluated by an athletic trainer or medical professional on the sideline.

Keep the athlete out of the practice or game on the same day as the injury, and do not let them return to play until cleared by a medical professional. “When in doubt, sit it out.”

Inform the athlete’s parent or guardian about the injury.

Obtain written instruction or communication from the athlete’s medical provider about a return-to-play plan. Follow the steps as written, check in with the athlete about their symptoms, and do not pressure them to do more than they can. Before an athlete can fully return to sports, they should have fully returned to school, not have any new or increasing symptoms when doing activities, and should have official clearance from their medical provider to return to sports.

Looking for more resources? Here is a factsheet about concussions made for coaches. Check out this concussion training course for coaches.

Related Blog Posts

Check out these blog posts to learn more about concussions across populations.

Suicidal ideation and concussions in high school students

Female specialized athletes and history of concussion

Medical ‘gaslighting’ of women and people of color

Post-concussion changes in menstrual cycles

Premature return to play consequences

Resuming physical activity 72 hours post-concussion benefits